COURSE CONTEXTS

-

Talk by Cole Swanson and Laking/Calcination process

During my residency in Transmission: A Transatlantic Project, a talk by Canadian artist Cole Swanson introduced me to his use of natural pigments and oxides. His approach, particularly working in 'a way of giving back to the earth' and working with other region-specific oxides, deeply fascinated me and inspired me to begin exploring pigment-making using spices.For my first attempt at creating pigment, I chose spices I use regularly in my own kitchen: homegrown turmeric, Goan chillies, and a spice blend made by my grandmother.

I applied techniques of calcination and laking, which I learned during a workshop in the Methods and Materials room, led by Annie Marie Akkusah and Chelsie Coates from the Painting workshop.

The Process of Calcination and Laking:

Core Principle: Acid + Base = Salt + Water

Main Ingredients: Alum (Potassium Aluminum Sulphate), Potash (Potassium Carbonate), Distilled Water, Chilli powder

Recipe:

-

Add 10g of chilli powder to a beaker.

-

Add 300g of warm distilled water and simmer for 30 minutes.

-

For neutralisation, use a molar ratio of approximately 2:3 (alum:carbonate), i.e. 2.2g of alum to 1g of potash.

-

Add 8g of alum and simmer for 20 minutes.

-

Sieve out any residue and collect the extract.Remove from heat and slowly add 3g of potash.

-

Allow the mixture to steep.

-

Let it sit for a day, then pour it into a filter paper to drain the excess water.

-

Allow the pigment to dry for 4–5 days.

-

Once dry, grind and store the pigment.

I was working with my peer, Alice Payen, during this process. She worked with a spice blend made by my grandmother, while I used the chilli powder. My choice to use chilli powder was influenced by a passage from Alex Rhys-Taylor in Cosmopolitan of Belonging, where he discusses how chillies, now a staple in many London households were once brought from South America by European colonisers and transported to India and South Asia as part of colonial trade networks.

Further research revealed that chillies were introduced to India by Portuguese colonisers who brought them from South America. Goa, then a Portuguese colony, was the first region in India where chillies were planted. This discovery intrigued me, especially as it highlighted how colonising forces played a pivotal role in shaping culinary, cultural, and social identities in colonised lands because even today, Portuguese influence remains deeply embedded in Goan food, language, and architecture.

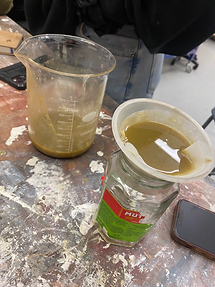

boiling the spices

measuring ratios

filtering process of spice blend

filtering process of chilly powder

filtered pigment ready to grind

2. Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location (2015)

In Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location, edited by Emma Jackson and Hannah Jones, the authors explore how belonging is shaped through emotional and spatial experiences, especially in the context of contemporary urban life. Suzanne M. Hall’s chapter, “Migrant Margins: The Urban Life of Street Corners,” focuses specifically on the neighbourhood of Walworth in South London, revealing how migrant and working-class communities form attachments to place through everyday practices, interactions, and intimate forms of inhabiting space. Hall argues that belonging is not just about legal or cultural inclusion, it is lived and felt in the textures of the street, in the rhythms of small businesses, and in shared social spaces.

Yet, this sense of home is often marked by ambivalence, as these communities exist under the looming threat of displacement through regeneration and gentrification.Hall uses the concept of “marginalized cosmopolitanisms” to describe how people navigate multiple cultural identities while rooted in specific, often precarious, urban locations.

These cosmopolitanisms are not elite or global in the traditional sense; they are grounded in localized, everyday experiences, like speaking multiple languages at a corner shop, or displaying goods from across the world in a small storefront. Importantly, she emphasizes that emotion and location are co-constitutive: how people feel (safe, threatened, welcome, invisible) is shaped by where they are, and how they belong there.

This book deeply impacted how I understand my place in the world and how I process those feelings through my work. It helped me realise that belonging is not only about where we are, but how we emotionally inhabit that space. This awareness allowed me to draw connections between my surroundings and my intuitive creative processes; like the passage from chapter two by Alex Rhys-Taylor on colonisation history led me to working with chilli pigment or responding instinctively to materials and moments that once felt abstract but now hold deeper meaning.

Suzanne Hall’s reflections on life in Walworth resonated with me especially, as this is an area I move through almost daily and often use as a reference in my visual work. Her writing gave language and depth to the quiet, everyday life I observed and documented, lending weight to the streets, faces, and rhythms I already felt connected to, and made my engagement with these spaces feel not only personal, but significant.

3. Transmission Residency group discussions

One of the most valuable aspects of the Transmission talks was the collaborative discussions we had with our peers. We were divided into groups of five, and at first, none of us were familiar with each other’s practices.

Yet, we had to collaborate and develop a shared outcome for the final show.Our discussions began with something simple and relatable, transport systems in London and Canada. We talked about our personal relationships with these systems, how we had grown around them, and how they physically and emotionally connected our two locations, despite the geographical distance.

As we continued these weekly conversations, we began sketching ideas and noticed how subway and underground maps resembled the branching flows of river channels. This observation led us into a deeper conversation about underground rivers; how these waterways, once vital transport routes for people, animals, and plant life, had now been replaced or built over by modern railway lines.Through further research, we discovered that places like Kensington Gardens once had underground rivers running beneath them, which are now replaced by parts of the London Tube.

I found this particularly fascinating, especially because I was regularly travelling on the Tube myself. I often documented the scenes I witnessed; reflections of urbanisation, the rush and noise of the crowd, and yet, paradoxically, a strange sense of silence, emptiness, and loneliness amidst it all.

While I was back in India, I also documented the railway transport system of Mumbai, one of the busiest cities in India. The trains were packed with people, far less structured or “sophisticated” than London’s, but they felt completely different. There was a certain rawness and human energy to them that lingered with me.

Around this time, I was also reading 'Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist, and was struck by his project : 'Cities on the Move (1997–2000)', co-curated with Hou Hanru. It was exhibited in multiple cities: Vienna, Bordeaux, New York, Bangkok, and brought together artists, architects, designers, and theorists to explore how migration, infrastructure, and visual culture were transforming urban life, particularly in Asia. What fascinated me was the open-ended format of the exhibition, it adapted to each location, not only in content but in meaning. It challenged dominant Western perspectives on urban development and highlighted how rapidly developing Eastern cities were reshaping those narratives.This project deeply influenced the direction of my work.

For our group show, I created a video projection that layered audio of flowing rivers with recordings from the Indian railways and London Underground. I had also planned to recreate a similar sound and video installation for our exhibition at Stackt Market in Toronto, especially because a new underground line was being constructed directly beneath the exhibition space, but wasn’t possible due to certain restrictions. This project to me was a way to express this sense of movement, history, and transformation, how cities evolve, how we travel through them, and how they shape our inner worlds.

Installation image of display at Stackt Market, Toronto

Some notes from group discussions

4. Exhibiton by Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern

The exhibition by Do Ho Suh was deeply inspiring for me. This exhibition made me reflect more deeply on the emotional layers of place, memory, and material, ideas I’ve been exploring in my own work as well. I had been reading about his work since the start of this term, and seeing it in person brought a new depth to what I had only encountered through books and articles.

The exhibition explored Suh’s experiences of living in three different cities he once called “home” at various points in his life.For Suh, “home is not a fixed place or a simple idea, it evolves over time and is continually redefined as we move through the world.” This sentiment strongly resonated with me.

His works “Wise Man” and “My Homes”, made with thread embedded into paper, featured a figure stretched across the surface. It reminded me a lot of my own relationship with line work; the way I use lines to map emotions and memories. It also echoed the feelings I had when I first encountered Beltrán’s embroidered works.

One of the most powerful moments of the exhibition was a video projection on a large screen, documenting Suh’s former residence at Robin Hood Gardens, London E14. Using time-lapse photography, drone footage, and photogrammetry, he captured the building just before its demolition. The visuals revealed the remnants of life left behind, faded curtains, broken windows, worn tiles, these tiny details that become intimate memories embedded in concrete. I found it incredibly moving how these traces of domestic life were preserved, even in a place that was about to disappear.

The exhibition also featured an interactive installation titled “Nests,” made of polyester fabric and stainless steel. I was captivated by Suh’s choice of materials, the delicacy and intimacy of the fabric made it feel as though I was stepping into another kind of energy. Even though the structure was translucent and I could see my surroundings, being inside it felt like a different space altogether. Suh linked this to an ancient Korean fabric-making technique, adding another layer of cultural connection.

The objects of “home” on display felt deeply personal, yet universally relatable; things many viewers could connect with emotionally.Another work that stayed with me was a floor plan rendered entirely through graphite rubbing on plywood, representing the architecture of a home. It reminded me of my own process of sanding canvases, smoothing them to prepare for painting. There was something very grounding about that tactile engagement with a surface, something Suh seems to channel beautifully in his own way.

Wise Man,thread embedded on paper, 2023

My Homes, thread embedded on paper, 2010

Nest/s, Polyester fabric and stainless steel, 2024

Nest/s, Polyester fabric and stainless steel, 2024

Suh exploring the process of rubbing or sanding the plywood with graphite

Robin Hood Gardens, Video,colour and sound (stereo), 2018

Citations:

-

Swanson, Cole, 2025. Guest lecture for Transmissions Residency [Microsoft Teams meeting]. Held 14 February 2025.

-

Tate, 2023. Do Ho Suh: Walk the House. [exhibition] Tate Modern, London,1 May – 19 October 2025.

-

Obrist, Hans.U., 2014. Ways of Curating. London: Penguin. Chapter: Architecture, Urbanisms and Exhibitions, pp.121–126.

-

Hall, Suzanne.M., 2014. Emotion, location and urban regeneration: The resonance of marginalised cosmopolitanisms. In: H. Jones and E. Jackson, eds. Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location. London: Routledge, pp.31–33

-

Jackson, E. and Jones, H., eds., 2014. Stories of Cosmopolitan Belonging: Emotion and Location. London: Routledge.